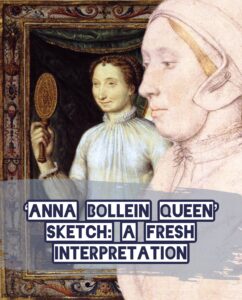

I consider myself lucky to have stood before The Royal Collection’s sketch labeled ‘Anna Bollein Queen’ and attributed to Hans Holbein the Younger, (1) twice in the last couple of years— once in New York City and again in Cleveland during the fantastic traveling museum exhibition, The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England. It was in the latter location where I overheard another visitor say to her companion, “This is Anne Boleyn? Not very attractive was she? Look at that chin.”

I consider myself lucky to have stood before The Royal Collection’s sketch labeled ‘Anna Bollein Queen’ and attributed to Hans Holbein the Younger, (1) twice in the last couple of years— once in New York City and again in Cleveland during the fantastic traveling museum exhibition, The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England. It was in the latter location where I overheard another visitor say to her companion, “This is Anne Boleyn? Not very attractive was she? Look at that chin.”

So of course I turned and looked, said nothing, but thought a lot of things. To be fair, I can understand her sentiment. Anne’s well-known persona sings more of a glamorous, elegant, and stylish queen and for that reason alone, some people believe the sitter in the sketch cannot be the iconic Anne Boleyn.

Before I get deep into my reasoning as to why I believe the sitter may be Anne Boleyn, I will address some of the issues often raised that negate the definitive identification of Anne.

- ‘Her hair is too light.’ To some this is a deal breaker in identifying the sitter as Anne, but I don’t think it has to be. Yes, Anne has been documented with dark hair but this sketch is nearly 500 years old. Colours of art mediums can change over time. The Tudors Art and Majesty in Renaissance England book published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York states, “The relatively crude application of yellow chalk to this part of the drawing, however, may well be by a later hand.” (2).

.

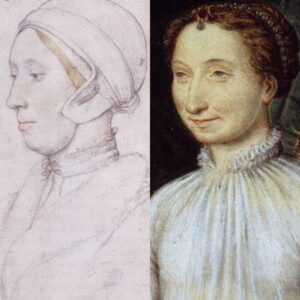

‘Anna Bollein Queen’ sketch layered over the Anne Boleyn Hever rose portrait with opacity adjusted for comparison. - ‘The double chin.’ I believe Anne may have been pregnant at the time of this sketch. As a mother, I can attest that before I even knew I was pregnant, I noticed my face shape changed. It was wider and there was some extra chub around my chin— not to mention the water retention on top of all that. Her chin is very believable to me especially as the elite did not routinely breastfeed (this burns a lot of calories). Also, if there is any truth to Nicholas Sander’s (nasty) remarks of a ‘wen’ on her neck, well, that might also be a reason for the double chin. Besides these, the sitter is looking down which will give just about anyone a double chin. (Go ahead and try it if you like. I took two side profile photos, and the ‘looking down one’ was too unflattering to post, proving my point about the chin.)

. - ‘It doesn’t look like Anne!” This may be a valid comment, or it may not be as technically there is only a single medal depicting Anne confirmed to have been created during her lifetime. This sketch, however, does remind me of the Hever Rose portrait Anne as well as several portraits of her daughter, Elizabeth.

.

‘Anna Bollein Queen’ sketch over a portrait of Elizabeth I in a similar pose with opacity adjusted for comparison. - ‘Wait, it’s a Wyatt.’ According to The Royal Collection Trust website, of all the Holbein sketches in their keeping, this is the only sketch with markings on the verso. (3) The second sketch is of the Wyatt family crest and some argue this may indicate the sitter is someone in the Wyatt family. I’ll explain later in this article why there may be an alternative Wyatt association.

Now, on to the fresh explanation (as far as I know!). A woman in her nightgown is not something often seen in 16th century portraiture. Some historians over the years have suggested that only someone with an elevated status like queen, could take such liberties with a portrait. I agree. The furs the sitter wears also indicate someone from an elite status.

Why is the sitter in a nightgown?

It is commonly suggested that the sitter may be Anne wearing a nightgown gifted to her by Henry VIII. That may be correct, though the look on the sitter’s face appears humble, and her eyes are downcast, which does not seem to correlate with the idea that this sketch was created for a seductive miniature (and yes, these did exist).

So what other reason would a woman wish to be seen in her nightgown? In Ruth Goodman’s fantastic book, How to be a Tudor, she mentions how people convicted by the Church of carnal no-nos such as adultery were often made to attend religious services in only their undergarments. (4) I do not think Anne Boleyn committed adultery, but I do believe the nightgown may represent her as a humble sinner. Let me explain.

The Tudors believed they were born sinners. You need only to read George Boleyn’s scaffold speech for an example of how people claimed to be wretched sinners. In George Boleyn: Tudor Poet, Courtier & Diplomat, Clare Cherry and Claire Ridgway write, “The Christian doctrine was that we are all sinners deserving of death because of original sin.” (5)

Anne was a Tudor. She was also a woman and because of original sin, women were said to suffer in childbirth due to Eve and her love of forbidden fruit. I believe Anne may have been pregnant in this sketch or perhaps it was after the loss of her unborn child (6). She would have also known the risks involved, not only concerning the gender of the baby, but that women of all statuses were at risk for dying during childbirth. Anne was no exception. I feel death would have certainly been on her mind with every pregnancy and likely a heightened sense of piety and religious devotion.

A nightgown depicted in a religious context brings to my mind words and themes such as ‘intimacy and personal prayer’, ‘triumph over ego’, ‘human morality and mortality’, ‘humble submission and humility’. I believe a depiction of a woman in her nightgown shows Anne as a devout Christian, who as a human is hopelessly flawed and a humble sinner, but who may be saved by the love of God and her faith in Him.

In addition, painters at this time were producing more and more accurate portraits, such as Holbein, and it seems plausible to me that Anne may have wanted to take this a level further and have a portrait created not of how others saw her, but how God may have viewed her. The focus of the sketch then may have been on the soul and less on the appearance of the sitter, similar to the old adage, ‘It’s what’s inside that counts’, but with devout, religious overtones.

Why have a sketch done like this at all?

Have you ever emulated something your idol did or been inspired by someone you admire? I feel like Marguerite de Navarre was a sort of role model for Anne. According to Eric Ives, Anne herself wrote in a letter to Marguerite in 1535, “her greatest wish, next to having a son, was to see you again”. (7) It is not known for certain if Anne served Marguerite during her time at the French court, but she would have certainly known of Marguerite’s religious and reformist works, and likely supported many of them as a reformer herself.

It is also likely that Anne acquired a copy of Marguerite’s poem Le Miroir de l’Âme Pécheresse, published in France in 1531. Examples exist showing Anne was in the habit of reading banned books and Marguerite’s caused a stir in France. The book was later translated into English in 1544 by Anne’s daughter, the future Elizabeth I, as a gift for Queen Kateryn Parr. (8) The English title is often quoted as either A Godly Meditation of the Soul, The Mirror of the Sinful Soul, or The Glass of the Sinful Soul.

The poem has themes of humbleness and sinful transgressions that can only be absolved by the grace of God. Its words aid reflection for the sinful souls of readers and focus on relationships to Christ through the female roles of mother, sister, daughter, and wife. (9) While exploring this work, I was quite intrigued by a painting of Marguerite which was from her brother King Francis I of France’s miniature book of hours. (10) The painting grabbed my attention because Marguerite is holding a mirror which made me think of her poem The Mirror of the Sinful Soul, but most significantly, she is dressed in a humble white nightgown. (11)

The painting dates to the 1530s, and the Holbein sketch dates to the early 1530s. Is it possible Anne saw this portrait of her idol and loved the idea? Was Anne inspired by Marguerite’s writings? Could Anne have been pregnant and wanting to represent herself as a humble sinner about to give birth? Or mourning a loss and feeling extra devout? The reformist slant of Marguerite’s works may have appealed very much to Anne as well as Marguerite’s cutting-edge style.

This theory would explain not only why the sitter in the Holbein sketch wears a nightgown, but also why her expression is almost somber with downcast, humble eyes.

What was the point of this sketch?

Even if the theme of the sketch was religious and not ‘saucy’, I can’t imagine a larger than life portrait of the Queen of England in her nightgown hanging on a palace wall. No, this must have been for a smaller project. A special portrait for Henry? Perhaps. A good luck charm for her labour? Probably not as sources indicate Anne was likely not superstitious. A token for her child if she passed in childbirth? Perhaps, but it’s not the most convincing. Then I realized the answer was staring me in the face. A miniature book of prayers similar to the use of Marguerite’s image. As a gift for Henry? Maybe, but maybe not.

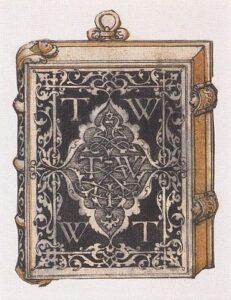

The British Library holds a stunning miniature manuscript of prayers with a portrait of Henry VIII inside (Stowe MS 956) (12). Popular legend tells of how Anne passed this gold encased girdle book to her ladies in her final moments while standing on the scaffold. While this story is amazing, yet almost impossible to prove, there is another miniature book of prayers that has been lost to time and involves the Wyatt family. Remember, the Wyatt’s family crest is on the back of the sketch.

A document from the Minutes of the Society of Antiquaries, written in 1725 by engraver and antiquary George Vertue, includes a sketch and description of the Wyatt manuscript, that has a history of being confused with the Stowe MS 956. (13) It has been said to have belonged to Anne Boleyn who gifted it to a member of the Wyatt family. (14)

The sketch of the miniature prayer book drawn in this document is described on the British Library blog as, “near-identical to a design by Hans Holbein in his ‘Jewellery Book’, now held in the British Museum.” (15) This is particularly interesting as Holbein is also the credited creator of the sketch labeled ‘Anna Bollein Queen’. The main difference is an inclusion of letters T, W, and I on the Holbein’s book design (see picture on the left), which may have been for a 1537 wedding between Thomas and Jane Wyatt, after Anne was already executed. (16) The Jewellery Book, which includes a collections of designs, including this book cover, was created by Holbein as an artisan pattern book. (17) Perhaps, Holbein designed the Wyatt manuscript cover during his patronage with Anne and adjusted the design as requested?

Another very interesting potential correlation between the portrait sketch and the Wyatt manuscript is that the latter’s 1725 description states: “This belonged to Q. Anna Bollen and now in the hands of Mrs Wyat of Charter House, in which family it has been ever since her death. She has like wise an original picture of her.” (18)

What original picture could Mrs. Wyat have? Original meaning extant? Original meaning unique? Both? Could this original picture be a small miniature portrait of Queen Anne Boleyn? And might the original picture of Anne be featured in a girdle book of prayers depicting her as a humble sinner in the style of her role model Marguerite de Navarre? Was the Holbein sketch of Anne in her nightgown created for miniature books of prayer? Oh how I would love to know!

Given as a gift?

If the miniature Wyatt manuscript was given as a gift to a Wyatt family member by Anne, who might she have given it to? It’s been stated that Margaret Wyatt, the court poet Thomas Wyatt’s sister, was one of Anne’s close friends. Did Anne give her ladies miniature girdle books? Or perhaps she gave the precious gifts to a select few of her closest companions. Or maybe a special copy was made for Margaret Wyatt for reasons unknown to us. Also, what might the Wyatt’s crest sketch have been used for if not the gold encasing on the book? Or is the Wyatt sketch only a reused piece of paper with little significance to the sitter on the verso? I do not have these answers, though I do think the many connections in this article may be significant and hopefully the mystery will lessen over time.

More on the Wyatt manuscript’s contents

Scholar Robert Marsham wrote of the Wyatt manuscript in an 1873 article entitled ‘On a Manuscript Book of Prayers in a Binding of Gold Enamelled, said to have been given by Queen Anne Boleyn to a lady of the Wyatt Family: together with a Transcript of its Contents”, published in Archaeologia, 44 (1873). (19) The transcript includes a multitude of prayers and psalms and there is a tantalizing possibility that Anne Boleyn may have authored or commissioned them. (20) While Anne defended herself at her trial, her speech was delivered full of meaning and poise. It seems to me that Anne was likely capable of writing such prayers and may have attempted to follow in the footsteps of Marguerite de Navarre and her many written works had her life not been cut short.

Regardless of the author, amongst the religious text within the Wyatt manuscript is this passage which I feel helps bring together the mystery of the sketch of Anne in her nightgown, the reformist words and portrait of Marguerite de Navarre, and the miniature Wyatt manuscript.

Within the second prayer of the Wyatt manuscript, it reads:

“Grant us, Lord, an humble and meek spirit, utterly distrusting on our wits, and calling to thee for wisdom, which art thyself wisdom and author of all wisdom, and which gives it to all folks that ask it of the steadfast and with faith. Grant us, Lord, to use it as a light and a looking glass to spy and amend our own faults, rather than to check, taunt and rebuke other men.” (21)

I find the use of the words ‘looking glass’ particularly telling as they reflect the words and portraiture of Marguerite, depicted as a humble sinner in her nightgown, holding a mirror. Dressed in humble attire of a nightgown, perhaps that does offer more reflection of one’s true self and soul than being distracted by all the pomp and frills of courtly dress. I also cannot help but think of Anne standing on the scaffold dressed to send a message to the crowd. Could this sketch of her in a nightgown be yet another way Anne used fashion to send a message to the viewers?

Summary

I believe the Holbein sketch of a Tudor woman in her nightgown and cap is Queen Anne Boleyn. I think it was likely created during or around one of Anne’s pregnancies after she had read Marguerite de Navarre’s Le Miroir de l’Âme Pécheresse and perhaps learned of Marguerite having her likeness painted wearing a nightgown. I believe the nightgown represents the attire of a humble sinner and is religious in context, possibly a reflecting an idea of God’s view of Anne. The placement of such a portrait of Queen Anne Boleyn would likely not have been on public display, but perhaps used in a miniature or girdle book of prayers. The ‘original picture of her’ associated with the miniature Wyatt manuscript, now lost to time, may have held the painted version of the Holbein sketch of Anne in her nightgown and the words inside may also belong to the Queen. This theory helps to depict a more pious version of Anne, and hopefully aids in diminishing the carnal staining she has been unfairly branded with for centuries.

Endnotes

- File:Anne Boleyn by Hans Holbein the Younger.jpg, Wikimedia Commons website. Accessed January 2024, https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Anne_Boleyn_by_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger.jpg

- Elizabeth Cleland, Adam Eaker, and Marjorie E. Wieseman (contributor), The Tudors Art and Majesty in Renaissance England. Published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Distributed by Yale University Press, New York, 2022, Page 216-217.

- Anne Boleyn (c.1500-1536), Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023. Accessed January 2024, https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/4/collection/912189/anne-boleyn-c-1500-1536

- Ruth Goodman, How to Be a Tudor: A Dawn-to-Dusk Guide to Everyday Life, Great Britain: Penguin Books, 2016, page 275.

- Clare Cherry and Claire Ridgway, George Boleyn: Tudor Poet, Courtier & Diplomat. MadeGlobal Publishing, 2014, page 286.

- I don’t like using the word ‘miscarriage’ as it implies some fault or failing of the mother.

- Eric Ives, The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2005, page 33.

- Claire Ridgway, ‘The Mirror of the Sinful Soul’, The Elizabeth Files website, published April 1, 2010, https://www.elizabethfiles.com/the-mirror-of-the-sinful-soul/

- ‘Marguerite de Navarre’, Poetry Foundation website, accessed January 2024, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/marguerite-de-navarre

- Miniaturist, French, Web Gallery of Art website, accessed January 2024, https://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/zgothic/miniatur/1501-550/1french/index.html

- File:16th-century painters – Portrait of Marguerite d’Angoulème – WGA15914.jpg, Wikimedia Commons. Accessed January 2024, https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:16th-century_painters_-_Portrait_of_Marguerite_d%27Angoulème_-_WGA15914.jpg

- Eleanor Jackson, ‘Fact-checking ‘Anne Boleyn’s’ girdle book’, British Library Medieval manuscripts blog, published June 14, 2022. https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2022/06/girdle-book.html

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Hans Holbein, Designs for Goldsmiths, Jewellers, etc., Arundel Society for Promoting the Knowledge of Art, London: 1869. Accessed January 2024, https://archive.org/details/DesignsForGoldsmithsJewellersEtc/holbein-h-designs-1869-BK001201-LowRes/mode/1up

- ‘Description and drawing of the Wyatt manuscript’, Minutes of the Society of Antiquaries of London, 24 March 1725, The Society of Antiquaries of London website, accessed January 18-21, 2024, https://collections.sal.org.uk/sal.02.001.223.

- Claire Ridgway, transcribed by Olivia Peyton, “The Wyatt Prayer Book”, The Anne Boleyn Files website. https://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/resources/anne-boleyn-words/the-wyatt-prayer-book/

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Sources

Anne Boleyn (c.1500-1536), Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023. Accessed January 2024. https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/4/collection/912189/anne-boleyn-c-1500-1536

Bryson, Sarah. “Childbirth in Medieval and Tudor Times.” The Tudor Society website. Accessed January 17, 2024. https://www.tudorsociety.com/childbirth-in-medieval-and-tudor-times-by-sarah-bryson/?amp=1

Cherry, Clare and Claire Ridgway. George Boleyn: Tudor Poet, Courtier & Diplomat. MadeGlobal Publishing, 2014.

Cleland, Elizabeth, Adam Eaker, and Marjorie E. Wieseman (contributor). The Tudors Art and Majesty in Renaissance England. Published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Distributed by Yale University Press. New York, 2022.

Darsie, Heather. ‘Marguerite of Navarre: Queen of the Renaissance’. Maidens and Manuscripts blog. Published May 13, 2017. https://maidensandmanuscripts.com/2017/05/13/marguerite-of-navarre-queen-of-the-renaissance/

‘Description and drawing of the Wyatt manuscript’, Minutes of the Society of Antiquaries of London, 24 March 1725: SAL/02/001 – Minute book, volume 1 (1718-1732), p. 151 © The Society of Antiquaries of London, https://collections.sal.org.uk/sal.02.001.223. Accessed January 18-21, 2024.

Goodman, Ruth. How to Be a Tudor: A Dawn-to-Dusk Guide to Everyday Life. Great Britain: Penguin Books, 2016.

Grueninger, Natalie. ‘Marguerite de Navarre and Anne Boleyn.’ On the Tudor Trail website. Published December 21, 2011. https://onthetudortrail.com/Blog/2011/12/21/marguerite-de-navarre-and-anne-boleyn/

Holbein, Hans. Designs for Goldsmiths, Jewellers, etc. Arundel Society for Promoting the Knowledge of Art. London: 1869. Accessed January 2024. https://archive.org/details/DesignsForGoldsmithsJewellersEtc/holbein-h-designs-1869-BK001201-LowRes/mode/1up

Ives, Eric. The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2005.

Jackson, Eleanor. ‘Fact-checking ‘Anne Boleyn’s’ girdle book’, British Library Medieval manuscripts blog. Published June 14, 2022. https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2022/06/girdle-book.html

Ridgway, Claire, transcribed by Olivia Peyton. “The Wyatt Prayer Book”. The Anne Boleyn Files website. Accessed January 18, 2024. https://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/resources/anne-boleyn-words/the-wyatt-prayer-book/

Vasoli, Sandra. ‘Anne Boleyn’s Girdle Book’. The Anne Boleyn Files website. Published Nov. 13, 2018. https://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/anne-boleyns-girdle-book-by-sandra-vasoli/

Image sources

- File:Anne Boleyn by Hans Holbein the Younger.jpg, Wikimedia Commons website. Accessed January 2024, https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Anne_Boleyn_by_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger.jpg

- File:16th-century painters – Portrait of Marguerite d’Angoulème – WGA15914.jpg, Wikimedia Commons. Accessed January 2024, https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:16th-century_painters_-

- File:AnneBoleynHever.jpg, Wikimedia Commons. Accessed January 2024. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AnneBoleynHever.jpg

- File: English School, circa 1560s, Elizabeth I of England, Wikimedia Commons. Accessed January 2024. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:English_School,_circa_1560s,_Elizabeth_I_of_England.jpg

- File:Design for a metalwork book cover, by Hans Holbein the Younger.jpg, Wikimedia Commons. Accessed January 2024. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Design_for_a_metalwork_book_cover,_by_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger.jpg

Further learning

See the Anne Boleyn sketch here:

Anne Boleyn (c.1500-1536), Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023. https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/4/collection/912189/anne-boleyn-c-1500-1536

Read the transcribed contents of the The Wyatt Prayer Book here:

Ridgway, Claire, transcribed by Olivia Peyton. “The Wyatt Prayer Book”. The Anne Boleyn Files website. https://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/resources/anne-boleyn-words/the-wyatt-prayer-book/

Hear more about Marguerite’s life and writings here:

Dr. Theresa Brock, Natalie Grueninger (host). ‘Episode 233 – Marguerite de Navarre: The Visionary Queen with Dr. Theresa Brock’. Talking Tudors podcast, 43 minutes. https://talkingtudors.podbean.com

Published on January 23, 2024.